|

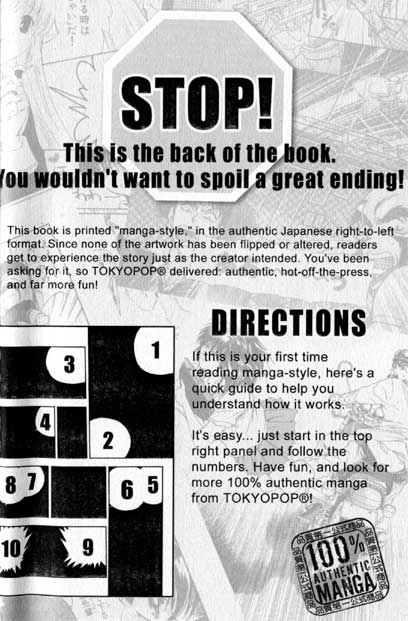

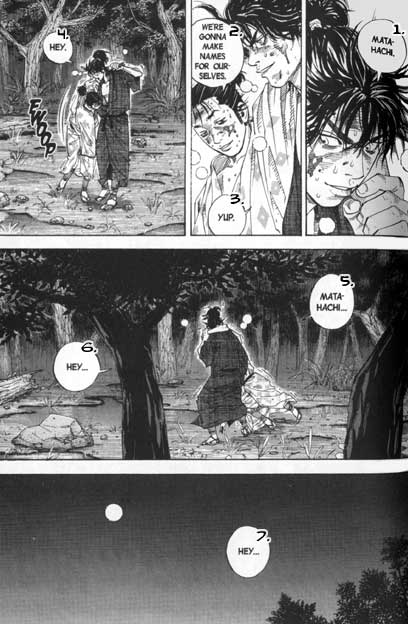

Just incase you don't know what manga is, how to read it, what things mean and are confused about doujinshi -I made this little section. The first part will be about: Japanese text format -This is how to follow the Japanese format even though the text is in english. It's pretty simple and many of the manga publishers in America have started doing things this way instead of the old mirror imaging way. I mean that way is fine for text but makes all right handed people look left handed. Here's some scans to help explain. This first one is from the back of one of my tokyo pop books:

See? It's pretty simple. Now here's a page from one of my favorite series "Vagabond" to help explain a little more: Just follow the numbers and you'll get the idea, just start at the top right bubble and work your way across. you get used to it really quickly and now every time I pick up an American comic I start reading it from the right side instead of the left, lol.

Next lesson is: Wait, wait, I'm not always great at explaining so lets do it this way, the "Ask John" letters at Animenation are great. I'm going to post a few here, but you should go see if more interest you. -Ask John Archive- So here we go, thanks John! These are great and I hope you don't mind me using these few ^_^; What's the Difference Between Doujinshi and Manga? March 21st, 2003 By ask John Q: What's the difference between doujinshi and manga? I thought I knew, but then my friend told me that Haibane Renmei is a doujinshi, even though the artist who wrote it wasn't using another artist's characters. Please explain! A: In very simple terms, doujinshi is independent or self-published manga. "Manga" is the name for Japanese comic art. Most of the time, though, fans think of manga as Japanese comics published by major publishing companies like Kodansha, Tsukasa, Seishinsha, Shogakukan, Gakken, Kadokawa, and many others. Doujinshi, on the other hand, are small press comics often printed and sold by the creators and artists themselves. Many western fans instinctively think of doujinshi as fan parody comics- amateur produced comics using established, famous anime characters. A large percentage of doujinshi do actually fall into this category, but there are also thousands of doujinshi published and sold in Japan each year that feature totally original characters and stories. Furthermore, doujinshi isn't just limited to amateur artists. Famous, professional manga and anime artists including Nobuteru Yuuki, Ken Akamatsu, Rikudo Koshi, Oh Great!, Johji Manabe, Kenichi Sonoda, anime director Shinichi Watanabe, and even the Morningstar Studio that created Outlaw Star and Angel Links still write, draw and publish their own doujinshi with their own money. Taking these factors into consideration, the single, universal defining difference between "manga" and "doujinshi" is the scale on which the comic is printed and who is behind the publishing. As a very loose analogy, "manga" would be akin to American comics from Marvel and DC while "doujinshi" would be considered "independent comics." Why Does Hentai Exist? Since some of my doujinshi are more adult themed I thought this letter would be informative April 4th, 2003 Q: What's up with hentai? Why was it created? For viewers to become gay and rape their girlfriends? Or entertaintment to see if Card Capter Sakura or Rei from Evangalion get screwed and last without screaming? It's not love, it's sex gone wrong! A: Given how frequently questions like this seem to come up, evidently there seems to be a lasting misunderstanding about hentai largely rooted in conventional Western attitudes about human nature, sexuality and children's cartoons. Anime if fiction. It's not real; it doesn't involve real humans; it doesn't involve real life. It's just colored drawings that move and make sound, or in the case of manga, it's just lines on paper. Largely, especially in America, it seems to be assumed that anyone that creates offensive imagery or who enjoys such material must be socially maladjusted or psychotic. Japan, seemingly unlike America, recognizes an interest in sex as a natural, instinctive human desire, and also recognizes that an interest in sex does not automatically equal or lead to sexual aggression or anti-social behavior. Especially in Japan, hentai is not "bad." It's just another genre of anime, no different from sci-fi, comedy, action or even children's films. Artistic, graphic depictions of sexuality in Japan date back hundreds of years. Pornographic "ukiyo-e" woodblock prints from the 17th through 19th century are now recognized worldwide as artistic masterpieces. As ancient Japanese art has evolved into contemporary manga and anime, naturally ancient Japanese depictions of sexuality would also develop and evolve into what Western fans commonly refer to as "hentai." The art of manga and anime exist to provide readers and viewers with an alternative to reality, a temporary entertaining escape. It only makes sense that a branch of this escapist entertainment would directly address the most fundamental and primal instinctive desire of mankind. (Naturally, the desire for sex is stronger than any other human instinct. If that was not the case, the human species would have become extinct eons ago.) Fantasy is defined as something that isn't real. Anime is fantasy because it presents people and worlds and events that aren't real. Just like any type of fiction, not all anime is intended or suitable for all viewers. Adult anime exists to appeal only to adult viewers. Westerners too often mistakenly assume that hentai is available to or intended for youngsters simply because it's animated. This is one of the lingering misunderstandings about anime in America that prove that anime is still not mainstream or widely understood in America. Adult anime is created by adults, available only to adults, and intended only for adults. Japanese artists comprehend that it's natural for adults to be interested in sex. These artists also recognize the anthropologically verified natural human instinct to be attracted to youth and vitality as a subconscious guarantee of the propagation of the species. Finally, these Japanese artists understand that there is a difference between fantasy and reality. Japanese society recognizes that it's natural for grown men to be attracted to young, cute females. It's a purely instinctive animal condition. Hentai manga and anime expresses and indulges this desire in a safe, non-harmful, socially acceptable way. As long as it's in comics and animation it remains fantasy, distinct from reality. To say that hentai is "sex gone wrong" is to apply Western morality to something that isn't Western. In one respect, hentai is love. Doujinshi featuring recognized anime characters exists because fan artists love a character so much that they spend their own time and effort to write and draw new stories with these characters. The fact that some of these stories may place anime characters in sexual situations gratifies the desires of fans. But while Americans may see the sexual fetishizing of anime characters as a form of disrespect to the original artists, Japanese fans see it as an expression of support, devotion and love of particular characters. American culture sees hentai as subversive and harmful, but Japan sees it as a harmless indulgence in pure fantasy. It's not my intention to begin a debate over the psychological effects of pornography or women's rights or unproven speculation, however it's important to remember in a discussion of hentai that Japan is home to the world's greatest amount of comic and animation pornography, yet Japan has one of the developed world's lowest reported per capita rates of sexual crime. Grossly exaggerated armchair science would seem to suggest that at least in Japan, hentai actually reduces sexual violence in society rather than contributing to it, as many Westerners would likely guess. In simple summation, hentai anime and manga is created for Japanese adults, not for children, and not for Americans, although many American adults do also partake of it. If you find yourself offended by adult anime, simply avoid it. Millions of Japanese citizens encounter adult manga and anime every day with no complaints. An American citizen accusing a Japanese art form of being prurient and obscene based on American cultural values and morals is simply being narrow minded and occidental, unwilling to accept the idea that other countries have moral values and cultures that are different but no less valid than our own. Why is There so Much Homosexuality in Anime? Manga in this case, I included this since some people think Link is gay or is strangely attracted to Sheik - also includes what "bishonen" are. December 23rd, 2002 By ask John Q: I'm a huge anime fan, but over half the anime I find includes homosexual scenarios, not that I'm complaining. But what is with that? A: What constitutes "homosexual scenarios" varies from viewer to viewer, and countless fans have a tendency to interpret dramatic character revelations from very ambiguous nuances. In fact, excluding pornographic hentai anime and homosexual themed anime titles, there are relatively few overtly homosexual characters in "mainstream" anime relative to the total number of major anime characters in the history of anime. There are numerous examples of same sex attraction, and numerous examples of male characters with pronounced feminine characteristics, but taken in context, these examples do not reflect homosexual personalities. Because Japan is an island nation surrounded by salt water, fresh water has always been a commodity in Japan. Thus Japan has an ancient history of communal bathing. Anime titles including Love Hina, Photon, Megazone 23 Part 2, eX-D and Mahoromatic include sequences of female anime characters in a shared bath comparing breast size. However, taking into account Japan's frank openness regarding sexuality and the natural human condition, scenes like this do not and are not intended to represent homosexuality. These instances are examples of teasing and playful jealousy, not sexual desire or physical attraction. Likewise, Tina Foster of Ai Yori Aoshi, for example, shows a marked attraction to females and female anatomy; however, Tina is not overtly homosexual. Characters like Tina are attracted to the physical beauty of the female form but seemingly have no interest in actual lesbian romantic relationships. This sort of attraction is similar to the "idol worship" seen in titles like Card Captor Sakura, Revolutionary Girl Utena, Brother Dear Brother, and Azumanga Daioh. Characters like Tomoyo Daidouji and Kaorin from Azumanga Daioh idolize the qualities of fellow female classmates, but this "hero worship" doesn't involve actual sexual desire. It's easy for fans to interpret characters like Tomoyo as being gay, but the actual animation itself provides no evidence of this conclusion. In a similar fashion, numerous Western fans frequently confuse the concept of "bishonen" beautiful and effeminate men, and cross-dressing male characters, as homosexuals when such a link is not always justified or even accurate. For example, the male Ladios Sopp of Five Star Stories is frequently mistaken for being a woman, however, in a famous sequence from the F.S.S. manga that was somewhat marginalized in the motion picture, Sopp unmistakably clarifies that although he may dress and look like a woman, he is totally heterosexual. Likewise, although Maron Glaces of Bakuretsu Hunter is very effeminate, he is never shown expressing any attraction to another male in any of the Bakuretsu Hunter animation, although he does develop an mutual attraction to a pretty young woman in the TV series. Bishonen characters are often more uninhibited about their personalities, but being expressive doesn't make one homosexual. If we exclude adult anime titles and series like Fake, Nagekino Kenko Yuroji (F3), Kizuna, Zetsuai 1989, Gravitation, and Yami no Matsui, there simply aren't that many overtly homosexual anime characters. My list will be incomplete, but at only little more than a half dozen titles, the number of overtly homosexual characters I can think of accounts for only a fraction of a percent of all anime characters. Hanagata of Saber Marionette J Fatora, and Alielle of El Hazard Aburatsubo of Maho Tsukai Tai Daley Wong of the Bubblegum Crisis OAV series Zoecite & Malachite, and Michiru Kaiou (Sailor Neptune) & Haruka Tenou (Sailor Uranus) of Sailormoon Sepia & Cobalt of Iczer-One The bi-sexual Milphey Yu of Bakuretsu Hunter OAV 2 (Griffith of Berserk seems to have no personal sexual preference, instead being bi-sexual only as a means to an ends) Simply given the sheer amount of anime that exists, and its cinematic diversity, the rule of percentages necessitates the existence of homosexual anime characters. And while same-sex teasing or innocent "homosexual scenarios" may occur frequently in anime, they do not reflect examples of actual homosexuality. These occasional sex jokes or character types are a subtle example of Japanese culture within anime. These instances are a reflection of Japan's open, humanistic acceptance of sexuality, which stands in contrast to America's largely puritanical subjection of natural sexuality. Most anime fans that think little of same sex dalliances, or ambiguous sexuality in anime do so as a result of their own amicability. Especially experienced fans often take no special notice of same sex actions or ambiguously sexual characters because years of viewing experience has placed these elements in relative context as a natural part of anime, no more unusual than any other aspect of anime. I can only suggest to viewers who find themselves offended by this content, either accept it as an element of Japanese culture within imported Japanese animated film, or simply refrain from watching imported Japanese animated film. What does "Omake" Mean? Since you will find this term on many Zelda sites August 12th, 2002 By ask John Q: What is omake? On the Blue Seed DVD box set there is an Omake Theater, and for the Fushigi Yugi OVA there seems to be a similar omake-ish collection in between the episodes. Is Adventures of the Mini-Goddess just omake? A: The Japanese word "omake" may be translated as "bonus" or "extra." Because features like non-credit opening and closing are often considered standard supplemental features on most Japanese home video release, the classification "omake" is usually reserved for extra special bonus animation or supplemental original animation supplemental to a longer work such as the examples you've mentioned, the SD Welcome to Lodoss Island segments of the Lodoss War TV series, the SD segments added to some episodes of To Heart, the science lessons in Gunbuster, and the parody segments added to the Japanese home video release of the Secret of Blue Water TV series. The SD Ah! Megami-sama anime was part of the longer Anime Complex anthology program, but is not "omake" because it's not a supplemental bonus added to any other show. What Started the "One Guy Many Girls" Trend? Can any one say OoT Link? LOL May 6th, 2002 By ask John Q: A lot of anime seems to revolve around a normal male protagonist surrounded by beautiful women who may or may not be competing for his affection. Examples of this include Tenchi, Love Hina, Dual, and numerous others. Where did this concept come from? What anime was the first to truly start this trend? A: As far as I'm aware, the earliest anime series to use the idea of one male surrounded by a bevy of bishoujo was the 1981 romantic comedy Urusei Yatsura. While hapless Ataru Moroboshi rarely found himself actually the center of massive female attention, his constant wooing of Shinobu, Sakura, Benten, Ran, Oyuki, Ryunosuke, and occasionally even Lum, is probably the first time an anime series used the concept of one boy surrounded by women as a plot device. Romantic triangles have existed in fiction since the beginning of literature itself. The earliest major example I can think of is the relationship of Amuro Rei, Char Aznable and Lalah Sun in the 1979 Mobile Suit Gundam TV series. It was virtually inevitable that eventually an anime would take the concept of a love triangle, and the seminal influence of Urusei Yatsura, and simply expand the two themes by adding a few additional characters. This evolution occurred in the early 1990s with a virtually simultaneous pair of events. The modern "bishoujo game" came into existence in the early 1990s, placing a player in a game with the goal of bedding as many fictional game gals as possible, with the ultimate goal being the selection of a single mate and a happily ever after ending. These erotic computer games doubtlessly influenced the creation of Tenchi Muyo in at least some subtle degree. (It's also very possible that the 1988 Ah! Megami-sama manga series had an influence on the creation of Tenchi Muyo, but the first Ah! Megami-sama OAV was not released in Japan until a year after the premier of Tenchi Muyo.) The 1992 Tenchi Muyo OAV series seems to have originated the shy guy/lots of girls theme that has become a virtual anime cliché. Like the computer bishoujo games of the time, Tenchi Muyo was obviously intended for a young male audience that took to the idea of being a single male surrounded by a host of attractive young women. Tenchi Muyo simply introduced the concept, and executed it so well, that like Gundam's introduction of mobile armor, Dirty Pair's use of scantily clad girls with guns, and Pocket Monster's concept of collecting something, the idea of one guy in a house with lots of girls turned into a genre cliché virtually overnight. While Tenchi Muyo, Pokemon, Gundam and Dirty Pair were all simply evolutions of previously existing themes, they each struck a chord with viewers and created virtually instant genre conventions that were immediately picked up and utilized by other series. Tenchi Muyo creator Masaki Kajishima returned to his concept of one man surrounded by women with later projects including Dual and Gosenzo-san E (the adult anime series released in America as "Masquerade."), and series including Happy Lesson, Sister Princess, Tenshi no Shippo, Kanon, Love Hina, Hand Maid May, Hanaukyo Maid Tai, Steel Angel Kurumi, Ah! My Goddess, Saber Marionette, Geobreeders, Nadesico, and probably many more than I'm forgetting. While it may seem too obvious that Tenchi Muyo was the first anime to use the "one guy many girls" set-up, Tenchi Muyo, in fact, could be argued to be the single anime that marked the change from the shonen, action oriented anime of the 1980s to the more domestic comedy and shoujo heavy 1990s. The years leading up to the 1992 premier of Tenchi Muyo are characterized by series including Secret of Blue Water, Lodoss War, Cyber Formula GPX, Tekkaman Blade, Nuku-Nuku, and Yu Yu Hakusho, and magical girl or school life shoujo series including Hime-chan's Ribbon, Sailormoon, Miracle Girls, Yadamon, Oniisama E..., Yawara, and Kingyo Chuuihou. The "one guy many girls" plot device that's so common nowadays simply did not exist before Tenchi Muyo introduced it in 1992. Can You Explain Manga Being Reversed? This explains a little more about the reading styles March 12th, 2002 By ask John Q: I noticed that when I read some of the manga series that have been turned into shows then watch the anime, stuff seems backwards. Pieces of armor will be on a different side, or an ornament or piece of jewelry on the left will then be on the right, also injuries or scars will be on the opposite side. I was wondering exactly why that is, and which way then, it is supposed to be. A: English language is designed to be read from left to right. Japanese language is typically read from right to left. In the original Japanese format, manga open from the right and progress to the left- exactly the opposite of English language books which begin by opening to the left and reading to the right. For the convenience of American readers that are used to starting a book on the left, most manga brought to America is "flipped," meaning that the panels are flopped upside down to face the opposite direction that they originally did. This way, the original right-to-left format appears as left-to-right, the way English language readers comfortable with. However, this mirror-image reversal makes things originally on the left appear on the right, and vice-versa. Usually this isn't significant or noticeable, however it does stand out particularly in the Gunsmith Cats manga translation, in which cars in America suddenly drive on the opposite side of the road because the art has been "flopped." There are exceptions to this policy, the most well known being Blade of the Immortal. Dark Horse Comics typically "mirror images" its manga translations to read left-to-right, however Hiroaki Samura, the creator of Blade of the Immortal, expressed a desire that his manga art not be altered for its English translation. In a compromise, whenever possible the English language translation of Blade of the Immortal literally copy and pastes the individual panels to retain the original Japanese look of the art in Western format. Perhaps the first manga translation to not compromise its panel layout for the convenience of Western readers at all was the Toys Press publication of the Five Star Stories manga in America, which includes a warning alerting readers to not buy the comics if reading right to left is too foreign and uncomfortable. Viz Communications published the Evangelion manga both ways. The standard edition Evangelion comics and collected graphic novels have "flopped art" while the "Special Edition" volumes are published with their Japanese format intact. And now TOKYOPOP, in a move to present the most authentic possible American presentation of Japanese manga, has announced that all of its forthcoming manga translations will be printed exclusively in their original, unaltered Japanese right-to-left format. What Are Fansubs? Parts of this can relate to fan translated manga, and how I feel about having manga on my site. I just want people from out side Japan to be able to enjoy it! December 27th, 2001 By ask John Q: My daughter and I want to know, "What's a fansub?" We've heard a lot about them; we just don't know what they are. A: A "fansub" is a subtitled version of an anime show produced by private, amateur anime fans on a non-profit basis. Individual anime fans buy an import anime tape, laser disc or DVD, or use an episode recorded off Japanese television, and translate the dialogue and add subtitles to the show on their home computer. Copies of this subtitled version are then given away for free or provided to anyone that asks for a copy, so long as the person asking pays the cost of the blank tape and postage. This is technically illegal since it is public distribution of copyrighted material without permission or payment of proper royalties to the copyright owner; however, both Japanese and American companies generally overlook fansubs because, in accordance with established "fansub ethics," fansubs are entirely non-profit and only shows and series that have not been licensed for American distribution are to be fan subtitled and dispersed. The purpose of fansubs is to allow American fans to experience new anime and use this experience to petition for particular shows to be licensed for American release. The goal of fansubs is to increase awareness of anime and Japanese culture. Fansubs exist to allow English speaking anime fans an opportunity to watch and enjoy translated anime that they would not otherwise have access to. Series including Fushigi Yuugi and Rurouni Kenshin were licensed for official American release in part because they were so popular in the fansub community. Fansubs have gotten a bad reputation not because they are technically illegal distribution of copyrighted material, but because too many unscrupulous people have taken advantage of the generosity of the fansubbing community and anime fandom. Too many people have been known to sell fansubs for big profit, and too many ignorant or selfish people have continued to translate and distribute fansubs of titles that have been licensed or even already legally released in English. The purpose of fansubs is to share import anime with other anime fans, not to substitute for or undermine the success of legitimate, legal, licensed anime translations. Unfortunately, bootlegging and fansubbing for profit have become synonymous with the philanthropic goal of non-profit fansubs in the minds of many observers. Fansubs of licensed titles should never be shared or distributed for any reason. Fansubs should never be sold, rented or distributed for profit. And fansubs should be replaced with legitimate, official copies if & when such become available. To ignore these basic tenets is to contradict the very definition of "fansub." With these guidelines in mind, you can find "digital" fansubs in PC video formats through IRC or other internet methods. Traditional VHS fansubs are available through the AnimeNation Links Page and the Anime Web Turnpike. Why Are Anime Guys Shy? For all you people who find Link a little shy around the girls. January 23rd, 2002 By ask John Q: [The following are separate but similar questions from two different readers.] I was just wondering why in some anime series like Tenchi Muyo and Evangelion the main male characters is so embarrassed about his sexual feelings? In Evangelion, what's going on between Shinji and, well, everyone? I haven't seen too much of the show, but in the part of the series I have seen, I can't tell who he's going for: Rei, Asuka, or Kaoru. A: Part of the point of Evangelion is that Shinji himself doesn't know who he's attracted to. This is actually one of the crucial, most fundamental elements of Evangelion, and unfortunately a point that many Western fans don't comprehend because Evangelion is addressed to and has a significant relation to specifically Japanese viewers. Contemporary Japanese teen culture has been traditionally characterized by a degree of de facto sexual segregation that's usually only hinted at in anime. Because so much pressure is placed on Japanese children to study and prepare for school entrance exams, it's common for Japanese teens to be alienated from and almost totally ignorant of social conventions regarding the opposite sex. Examples of this appear in anime most commonly in the presentation of groups of guys hanging out together and girls spending time in groups of other girls more so than mixed gatherings, and the occasional "How To Sex" manuals that appear in anime to explain the "dos and don'ts" of dating and sex. Series featuring shy or introverted male characters, or shows that feature boys that are afraid of women, such as Evangelion, Hanaukyo Maid Tai, Tenchi Muyo, and Love Hina, are intended to represent this stereotypical Japanese teenager who is awkward and uncomfortable because of his natural attraction to the opposite sex, but afraid of his ignorance. In Tenchi Muyo, the girls seem to have little trouble in expressing their emotions and attraction toward Tenchi, possibly because they are aliens, but the native Japanese Tenchi Masaki is shy and timid around the girls. Likewise in Love Hina, the girls all show no inhibitions around each other, but are disturbed, confused and awkward around the male Keitaro. Likewise Keitaro is insecure and unsure of how to act around the Hinata-sou girls. Evangelion addresses this social segregation by making Shinji an "everyman" representative of contemporary Japanese youth culture- alienated, self-conscious, insecure, and suffering a sense of lack of identity. One of the main points of Evangelion was to show young Japanese boys that this fear and uncertainty was normal and a natural part of adolescence. In fact, the main point of Evangelion itself is to address the fear of alienation and loneliness and validate it as natural and even necessary for survival. Not only Shinji, but every major character in Evangelion suffers from some sort of alienation. Shinji has lost his mother, hates his father, and is afraid of commitment to anyone else. Asuka both hates and loves her mother, and partially blames her loss on herself. Misato tries to replace her lost father with a string of lovers. Ritsuko replaces her mother figure with computers. Maaya suffers an unrequited love for Ritsuko. Gendo is alienated from his son and wife. Rei cherishes her familiarity with Gendo, but that relationship is one based on pride rather than affection. The entire Seele network seeks to eliminate loneliness and isolation through the Human Instrumentality Project by uniting all life into a single entity. The conclusion of the Evangelion TV series, original TV episodes 25 & 26, explains that isolation is individuality. Alienation isn't what causes lack of identity; alienation is what identifies the individual as different from someone else. Alienation, in fact, creates identity. Shinji is confused about who he loves because he's afraid to choose one person and thus distance himself from the people he didn't choose. He pilots the Unit 01 because he believes that as long as he does so he will be recognized as "pilot of Unit 01 Shinji Ikari." He fears that if he isn't "pilot of Unit 01 Shinji" he won't be recognized at all, and won't be anyone at all. Evangelion tries to show Shinji, and Japanese teenagers, that only by making choices and decisions does individual will develop. As long as one tries to be everything for everyone, one is, in fact, nothing. As long as Shinji is the Unit 01 pilot he isn't "Shinji," he is just "Unit 01 pilot." It is at the end of the Evangelion TV series, when Shinji begins to comprehend a life devoted to himself or one person, when he and the other characters realize that their solitude isn't a curse but actually the source of their strength and willpower, that he is congratulated for his progress and maturation from a "spineless" cipher child to an adult with the ability to make decisions for himself and recognition of himself as a viable, worthwhile individual person. Can You Explain "Doujinshi Circles?" Really nice info about Circles and about what Doujinshi is December 17th, 2001 By ask John Q: I'm interested in joining a doujinshi circle in Japan one day. How, exactly, does one join a doujinshi circle? Can it be considered a real job or a hobby? Also, can a doujinshi artist be sued by anime companies for copying their characters? Does this sort of thing happen a lot? A: By definition doujinshi are Japanese fan produced manga comics or animation. That means that technically, to produce doujinshi, you have to be in Japan, and your doujinshi has to be a self-published or small press production. But that's not to say that Americans can't produce doujinshi. In a loose sense, anyone that's ever drawn his/her own fan art manga has produced a doujinshi, and small press publications like the hentai Dirty Pair comic "Nostalgia," are examples of true American created doujinshi. Writing and drawing doujinshi is a hobby, not a profession. Artists that start off drawing doujinshi and later make a living out of it, like the ladies of CLAMP for example, aren't doujinshi artists any longer, they're professional manga artists. A "doujinshi circle" is simply the name for a group of friends that work together to produce their amateur manga. These fan produced comics are sold to other fans, and may even be sold through doujinshi stores like Comic Toranoana, but they're still amateur because they don't generate enough profit for the artists to live on. Joining a doujinshi circle is as easy as finding an established group willing to let you work on their comics or publish your art in their book. In fact, you and a small group of creative friends could get together, work on a comic and legitimately call yourselves a doujinshi circle. Doujinshi is such a massively popular hobby in Japan that there are chains of stores in Japan that sell only fan produced comics and the annual Comic Market conventions of self published and amateur manga only draw crowds in excess of 100,000 attendees. Video game company Leaf even dramatized the exploits of a fictional doujinshi circle trying to balance high school, comic conventions and creating doujinshi in the popular PC and Dreamcast game Comic Party, which was also turned into a 13 episode anime TV series. Since doujinshi is so popular in Japan, and so many professional anime artists have their roots in the "doujinshi scene," most creators and Japanese studios overlook doujinshi or consider it a form of flattery. Furthermore, since the people that create doujinshi are the same people that financially support the Japanese animation industry, it's natural for Japanese studios and distributors to be hesitant to threaten the very same customers their rely on to buy anime products. However, there have been instances of companies pursuing charges of copyright infringement against fans for using famous characters in fan produced comics. In 1999 Nintendo pressured Japanese police to arrest 32 old Yukie Michimori for distributing copies of a Pocket Monster (Pokemon) hentai doujinshi she created in which Satoshi (Ash Ketchum) rapes Pikachu. Nintendo charged Michimori with copyright infringement and "destroying the dreams of children." Why do Anime Characters Fall when Something Silly or Stupid Happens? September 24th, 2001 By ask John Q: I was wondering why anime characters fall over every time something silly or stupid happens? Like in the Dragonball series for example, Goku can be in the middle of a battle fighting and he can say, " Hey, can we have a food break? I'm starving!" and Piccolo, Krillin and company will all fall down. I mean, most likely, someone would say "Oh Goku," or "That's our Goku," or say something like that, but anime characters always fall. Why is that? A: Remember that most anime is based on manga- black & white comics, and that's where this sight gag may have originated. The most logical explanation is that because it may sometimes be difficult to illustrate shock or surprise from several different characters at once in comic art, the easiest way to represent this reaction is through an obvious visual pun or clue. In accordance with the visual storytelling style of manga, the most effective way to show characters "floored with disbelief" is to literally show them falling to the ground. Naturally it's not expected that this be taken as a literal representation of reality, just as no one would expect to see a light-bulb floating above the head of someone suddenly illuminated by a bright idea. Some manga and anime play with the convention by making characters fall over repeatedly, or by showing the characters getting back to their feet after falling over, but this is once again intended to be taken as exactly what it is- a visual gag, not a representation of "reality." Are Hentai, Ecchi and Doujinshi Different? Yes, know your terms and read on... June 21st, 2001 By ask John Q: I wish to know if there is any real difference between hentai, ecchi, and doujinshi manga. Are any of them in any way more or less *ahem* "vulgar" than the others, or are they just different names for basically the same thing? A: Technically there is actually a significant difference between ecchi, hentai and doujin manga. The easiest to address definition is that of doujinshi. Doujinshi are simply fan produced manga, often using famous anime characters from anime TV series or major professional manga. Most of the time the doujinshi that make it into the hands of Western collectors are pornographic fan produced "homage" to favorite anime series, but not all doujinshi are pornographic. Actually, only a relatively small percentage of the total amount of doujinshi created in Japan are actually pornographic, but these books simply aren't usually very interesting or collectable for Western fans that can't read Japanese. In a technical sense, there is also a difference between "ecchi" manga and "hentai" manga, ecchi manga being merely risqué while hentai manga is graphically pornographic and intended only for adult readers. As examples, manga series like Goldenboy, Iketeru Futari, Otenki Oniisan (Weathergirl Report), G-Taste and Futari ni Omakase are "ecchi" because they contain heavy sexual humor, exploitive shots and scenes and a heavy emphasis on sexual innuendo but relatively little actual physical sex. A lot of yaoi manga including Kizuna and Bronze may also be considered "ecchi" even though they may contain actual physical sex because their focus is not on erotic titillation but on style and sensuality rather than "vulgar" pornography. Naturally then, hentai manga can be thought of as the "hardcore" pornographic manga that contain graphic sexual situations, intended more for vicarious sexual gratification than "innocent" reading pleasure. Do Fansubs Influence What Gets Licensed? It's happened before it could happen again. I don't belive there is no market for the Zelda manga and if publishers knew that people wanted to see it I'm sure there's no reason it wouldn't be brought over -except Nintendo might want to much for the license. I mean, heck, the Zelda series is one of the number one selling game series of all time, so if there is a now domestic manga just for Street Fighter's Cammy, and a manga about a wok chef, then why can't zelda do well enough for the market. Anyone who says it wouldn't doesn't really understand the situation in my mind. June 14th, 2001 By ask John Q: Do major anime companies look at fansubs as a way to tell what to bring to America? Anime such as Gundam Wing, Card Captor Sakura, Kenshin, Fushigi Yuugi, Rayearth, Nadesico, and Dragonball Z all have fansubs of the complete series or at least most of their episodes, and all are in America already. Does this mean that other fan favorites (Marmalade Boy, Kodomo no Omocha, Macross 7) will have a chance at appearing on American TV? A: I can't speak on behalf of the domestic translating companies, but I can provide what information I've gathered in the past. Fansubs do have a significant influence on what does and doesn't get licensed in America. In fact, the connection between fansubs and licensed translations is one of the fundmental reasons for the existance of fansubs. Anime fans fluent in Japanese or having altruistic devotion to anime create fansubs in an effort to promote the Western release of deserving titles. Fansubs allow fans to see anime they otherwise wouldn't have access to, and generate interest in particular titles. Professionally licensing, translating and distributing anime is an expensive undertaking. To be successful, domestic anime companies have to select titles to translate that they're certain will have a market in the US. The best way to do this is to look to the fan community. If a particular anime series is widely disseminated in the fan community, there's probably a good chance that these fans will buy a professionally translated and mastered licensed version, and an equally good chance that mainstream viewers will also enjoy the series. Consider American licenses including Fushigi Yuugi, Utena, Rayearth and Rurouni Kenshin. In the case of FY and Utena especially, previous to these two shoujo titles, the only shoujo anime available in America was Sailormoon and the fringe shoujo Maison Ikkoku and Orange Road. It's unlikely that distinctly shoujo titles like Fushigi Yuugi and Utena, especially, would have ever come to America if companies like Pioneer and Central Park Media weren't aware that there was already a great deal of fan interest in both titles. The same applies to Rurouni Kenshin. It's difficult to imagine that a nearly 100 episode long animated political drama about 19th century Japan would ever find a market in America, but massive American fan support and widely distributed fansubs certainly helped pave the way for this series. To quote Kodocha Anime, "Fansubs are not cheap alternatives for store-bought tapes! Fansubs are brought to you for the purpose of helping build an audience for anime titles so that an American release can be possible." Fansubs make fans aware of what titles to ask for, and an professional translating company is certainly more likely to try to license and distribute a title that they know they have a market for than a purely untested, risky gamble. But the fansub market alone isn't enough to support the massive investment necessary to localize an anime series. You can extrapolate from the fact that both American and Japanese companies largely condone (by tacit approval) the existance of fansubber and fansub distribution and trading. This suggests that fansubs don't make enough of a significant impact on sales to be anxious about. Assuming that this is the case, we have to recognize that fan support for a title alone isn't always enough to see a series brought to America. Since the fan community is still a relatively small market compared to the total number of home video buying consumers in America, an anime title has to be marketable to mainstream, causal fans or non die-hard anime fans to be a viable commercial venture. Furthermore, a series has to be available for license from its Japanese copyright holder. In the case of Macross 7, while fan support of the show is relatively significant, the mere "Macross" name makes this an unusually expensive and difficult to approach license. In the cases of Marmalade Boy and Kodomo no Omocha, both series may be wildly popular among die-hard anime fans that are used to distinctly Japanese humor and shoujo family relationships, but would the average Joe on the street "get" Kodomo or be willing to take a chance on Marmalade Boy? Under present circumstances, possibly, possibly not. This is where fansubs come in. Using fansubs to introduce these potential consumers to shows like Kodomo for free today creates new fans that will be willing to spend money on a licensed version of the show tomorrow. What is Bishonen? October 31st, 2000 By ask John Q: What does the Japanese word "bishonen" mean? A: My pocket Japanese to English dictionary translates "bishounen" as "handsome youth." To be slightly more accurate, bishounen refers to beautiful men or boys. Its commonly accepted meaning is as a descriptive pronoun referring to a "pretty" boy. I`m not suggesting any sexism with this comment. By pretty boy I mean the "heart-throb" or effeminate character. It`s actually a bit difficult to accurately describe the character type without using examples, so allow me to present some. Bishounen heroes range from the violent and masculine protagonists of Gundam Wing and St. Seiya, to the effeminate Maron Glaces of Sorcerer Hunters and Ladios Sopp/Amaterasu of Five Star Stories. More excellent examples include Akio, Saionji and Touga of Utena, the Vampire Hunter known as D, Griffith of Berserk, Mephisto from Demon City Shinjuku, and Ryo of Devilman. These men have a certain sense of style and fashion, and also an air of mystery and regality about them. They are not like other men; they are either more aloof or more powerful. Even when they make mistakes, their mistakes or errors are trifling matters to them, not the stumbling blocks or embarrassing moments similar blunders would be to normal men. The bishounen character type is often associated with "shounen ai," also known as "yaoi," or homosexuality. The nature of the bishounen makes him well suited to sensuality. Especially the effeminate male character, who is both anima and animus, male and female, seems perfectly suited to a homosexual relationship. To research more about the "bishounen" phenomenon, allow me to refer you to the bishounen category of the AnimeNation links page. Why is there Christian Symbolism in Anime? Since there is a lot of christian symbolism in the zelda series I thought I would add this... July 6th, 2000 By ask John Q: Since Japan is a country which is only 10% Christian, how do the Japanese feel about Evangelion and its portrayal of a "foreign" religion? Why did Gainax choose to create a series based on Christianity? Furthermore, I was curious if you could explain if there is any significance to the appearance of "angel wings" on characters in anime. A: As far as I know, the reason behind the Christian symbolism that appears commonly in anime is due to the fact that Japan is predominantly non-Christian. The Asian religions, Bhuddism, Taoism and Shinto all are very minimalistic religions. Asian religions, largely, simply don't have the pageantry and regalia of Christianity: none of the ornate decorations, costumes or rituals. Because of this, the Japanese find Christianity to be a fascinating spectacle. Religion and myth have always been a part of anime, from the myth-inspired Horus: Prince of the Sun, to the Norse inspired Ah! My Goddess, Shinto influenced Blue Seed, Greek mythology based Arion, and Christian themed Evangelion, Angel's Egg and Tenshi ni Narumon, just to name a few examples. In all of these shows, religion isn't used as a background to anime in order to convert viewers. Religious background is used in anime almost exclusively in order to provide depth and story. Religion isn't used to prove some point; it's used because it makes a show or story more interesting. The appearance of angels in anime, or girls with angel wings, ranging from Rinoa in Final Fantasy 8 to to male "angels" of Earthian and Escaflowne are intended to express a degree of angelic innocence and pureness. Given the limitations of animation, it's much easier to present visual cues of character traits like "goodness" than it is to show subtle facial expressions or constantly use music or lighting effects. What Does "Otaku" Mean? Some people think Otaku is a bad word, some think it's a badge of honor, I guess it's all the same thing as if you would consider being called a geek a good or bad thing. I am proudly a zelda geek but -maybe- not at the level of an Otaku. June 15th, 2000 By ask John Q: Is it true that the word "otaku," used all around the world to refer to an anime fan, actually means "nerd" in Japan? A: The word "otaku" actually translates to "house." It was adopted as a reference to obsessive fans that lived with their collections and never came out of their homes into the sunlight in Japan. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, "otaku" was very much a negative, derisive term in Japan. Even now, when the stigmata of being an "otaku" has softened in Japan, and there are now Japanese "anime otaku," "car otaku," "gun otaku," "idol otaku," and such, it's still not a good idea for especially American tourists in Japan to refer to themselves as "otaku." Oddly enough, when the term came to America and then spread throughout the rest of the world, much of the negative connotation originally associated with the term got left behind. This may have something to do with the fact that very few of even the most devoted Western anime fans have a devotion to their hobby that compares to the obsessive fanaticism of true Japanese otaku. For good examples, look to (albeit fictionalized examples) the virtually obsessive-compulsive otaku in Gainax's Otaku no Video and "Mi-maniac" of Perfect Blue. Fans that memorize their favorite personality's blood-type, birth-date, shoe-size, idiosyncrasies and entire life-history can somewhat justify the suggestion of "otaku" referring to a psychologically unbalanced fanatic. What Is A Doujinshi? Febuary 24th, 2000 By ask John Q: What is a Doujinshi? Is it like Manga? Do you have any Final Fantasy 8 Doujinshi? A: Doujinshi is the Japanese term for fan-produced manga comics. Because Japan has a somewhat more relaxed attitude toward copyright protection, most anime creators and production studios tolerate fans producing and selling home-made comics that use established characters. Many creators actually consider doujinshi a form of praise. Titles like Final Fantasy or Tenchi Muyo that have many doujinshi incarnations merely prove that these titles are popular enough to lead many fans to draw their own comics staring these characters. Many of today's most famous anime creators, in fact, got their start as doujinshi artists, and some creators, like Kenichi Sonoda and Nobuteru Yuuki still release their own doujinshi books. While many doujinshi are simply new stories or side-stories thought-up and drawn by fans, a large number of doujinshi focus on placing famous anime characters in sexual situations, ranging from risque nudity to intense, hard-core pornography. Virtually every anime show and video game you can name has at least one doujinshi in existence. Since doujinshi are fan-produced books, they usually have a relatively small print-run and are typically more expensive than manga published by professional companies. Largely for this reason, AnimeNation does not commonly stock doujinshi books. AnimeNation carries several professionally bound volumes of adult doujinshi anthologies. The Paradise Lost and Angelic Impact series are collections of Evangelion doujinshi. The Lunatic Party series collects numerous Sailormoon doujinshi into keep-sake books. Why Do Japanese Characters Have Big Eyes? If you don't know who Osamu Tezuka is, do your homework ;) January 12th, 2000 By ask John Q: Why do Japanese characters have big eyes? A: The most commonly accepted explanation for the giant anime eyes phenomenon traces back to Osamu Tezuka, the creator of Astro Boy and Kimba, and the acknowledged "father" of modern Japanese animation. Growing up in American occupied, post-WWII Japan, Tezuka was heavily influenced by early Disney animation- particularly Mickey Mouse's wide, round eyes. Believing that Western culture was destined to dominate the world, Tezuka began to draw his own cartoon characters with large, expressive, Western eyes. His style set the precedent that virtually every Japanese manga artist and animator has followed in the 30 years since. Finished with that! Go to the Ask John Archive if you want to read more cool questions and answers. Here's a glossery of terms from one of my favorite japanese based sites:

|